Preface

The path I am about to describe is not one that I have forged on my own...indeed I am but a traveler, a participant in the current wielded by those who have come before me and who continue to inspire and guide my work. I would like to dedicate this post to them, my teachers; the late Margaret Colquhoun of Pishwanton, Keith Robertson, FNIMH of the Scottish School of Herbal Medicine, Maureen Robertson of The Herbal Path, and of course the brilliant Johann Wolfgang von Goethe himself, all of whom have taught me the value of learning to listen to the plants with soft eyes.

Scottish School of Herbal Medicine Class of 2006

I would also like to thank Thomas Easley of the Eclectic School of Herbal Medicine for allowing me to share this process, year after year, with his students. I am eternally grateful to the ESHM class of 2018-2019 who participated in this study of White Pine and who have graciously allowed me to share their work here. They were an amazing group to study with and I felt honored to be in their company as fellow travelers.

Before diving into the phenomenon of White Pine as we observed it this past summer (2018) at the Eclectic School of Herbal Medicine, I must provide a little context into what my process of a Goethean Plant Study entails and the philosophy whence it is derived. Novels have been written about Goethe’s way of science, and so naturally I can only touch upon his work and perspectives with brevity. And although I have practiced this process for over a decade, my grasp remains in its infancy.

This is a long piece of writing, so for those of you whom are truly interested, buckle up, or get comfortable, or whatever...this is going to be a journey.

Goethe: Wholeness & Science as a Human Act

From Goethe's Theory of Colours, 1810

Johann Wolfgang von Goethe was an 18th century German poet, writer, and philosopher who through his explorations of comparative anatomy, botany, geology, meteorology, and color, has become infamous and admired for his contributions to Western science; to the act of doing science and the philosophy and process behind this doing. Goethe had the balls and the prose to challenge the leading scientific minds of his time…another quite admirable quality. He is also acknowledged as a major influence behind the work of Rudolf Steiner and the Anthroposophical movement.

Goethe’s approach to doing science is more than simply ‘holistic’; it is ecological.[i] It goes way beyond the old adage ‘the whole is more than just a sum of its parts’ to acknowledge ‘the whole exists in each of the parts’.[ii] As the late Henri Bortoft once wrote,

“The key to understanding Goethe’s work in the science of the organic world is to recognize the specific quality of his way of seeing living organisms. It is as if Goethe turned our customary way of seeing inside-out.” [iii]

In my still youthful understanding of Goethe’s work, his way of seeing and doing science always seeks to observe a phenomenon, such as a plant, in relationship to the broader patterns of its expression in the natural world. As Craig Holdrege, Goethean Scholar of The Nature Institute notes,

“He was keenly aware of the errors that occur when we focus too exclusively on isolated details…because he had learned that in living nature nothing happens that is not in connection with a whole.” [iv]

Goethe wrote:

“With any given phenomenon in nature—and especially if it is significant or striking—we should not stop and dwell on it, cling to it, and view it as existing in isolation. Instead we should look about in the whole of nature to find where there is something similar, something related. For only when related elements are drawn together will a whole gradually emerge that speaks for itself and requires no further explanation.”[v]

And in a separate essay he states:

“Those human beings undertake a much more difficult task whose desire for knowledge kindles a striving to observe the things of nature in and of themselves and in their relations to one another.”[vi]

Johann Wolfgang von Goethe (1749-1832)

Goethe is also acclaimed for recognizing that the human condition and the act of doing science are inextricable from one another; that the scientific process is indeed a human process and as such, regardless of how much we tell ourselves otherwise, the scientist will never be able to completely remove themselves from any scientific act. As Holdrege states,

“Because Goethe realized that science is a form of interaction and participation in things, he was especially careful, methodical, and critical. He did not hold the naïve view – still widespread today – that science presents the one objective revelation of the ‘way things are.’ He saw the confusion and misunderstanding that arises when we don’t take the human knower and doer into account as part of the scientific process and product.”[vii]

However, Goethe also warns us of a potential folly:

“As soon as we perceive the objects around us we consider them in relation to ourselves – and rightfully so. For our entire fate depends upon whether they please or displease, attract or repel, benefit or harm us. This completely natural way of considering and judging things seems as easy as it is necessary. But is also makes us susceptible to a thousand errors that can shame us and embitter our lives.”[viii]

Yet in his view the human process of doing science also provides the scientist or observer with an opportunity for both intellectual and personal growth for it challenges our considerations, our perceptions, our way of seeing. He goes on to write,

“The more we expand our consideration and the more we relate phenomena to one another, the more we exercise the gift of observation that lies within us. If we know how to relate this knowledge to ourselves in our actions, we earn the right to be called intelligent.”[ix]

If intelligence is a reflection of knowledge, and knowledge is indeed desired, developing our gifts of perception and observation is infinitely powerful, and equally so in relationship to both phenomena and Self. In this process of doing science one learns to develop oneself through the development of one’s own power of observation. In addition, as one develops said gifts the human process of doing science (or the Western scientific method) evolves. As Holdrege reminds us,

“Goethe saw that progress in science depends upon the development of inner capacities and sensibilities—and not only on the ever further refinement of external instruments and methods and ever grander generalizations. You could say that it’s an effort to create a science that is itself more whole by integrating it into the whole—and that means the developing—human being.”[x]

A sketch by J.W. Goethe, 1774 Source: King's College, London

Through recognizing and accounting for its influence, Goethe’s way of science teaches us to honor being human as part of the wholeness of the scientific process. Indeed, it allows us to make room for the interdependency of science and humanity. In his book, The Wholeness of Nature: Goethe’s Way of Science, Henri Bortoft beautifully reminds us of the interconnectedness and interdependence between the observer and the observed,

“This is clearly a synergistic activity: the phenomenon depend on our human cognitive activity, as we in this activity depend on the phenomenon.” [xi]

This is what Goethe often referred to as ‘delicate empiricism’ (empiricism being defined as the theory that all knowledge is derived from sense-experience). For many involved in modern Western scientific inquiry, this approach is likely to be considered possessed by demonic bias. But as Goethean scholar Isis Brook wrote in her essay Goethean Science as a Way to Read the Landscape,

“One should not make the mistake of assuming that Goethe recommended a naïve or pre-critical view. Goethe accepted the essential role of the mind’s activity in rendering experience meaningful. What he disagreed with was Kant’s contention that what is revealed by the mind is not things as they are in themselves but only as they appear to the human intellect.”[xii]

The philosophical paradox of Goethe and Kant holds tension. Yet it is in this holding of the tension between such opposites where we may find wholeness in the Western scientific worldview. It is the quaternary, the squaring of the circle along the axes of evaluative and non-evaluative modes of perception.[xiii] No wonder Carl Jung loved Goethe’s work so much...

As an herbalist who endeavors to not only help improve the lives of those who seek my guidance but whom also attempts to continually develop a deeper understanding of myself and of the plant kingdom, Goethe’s way of science is teaching me to embrace and trust my observations as valuable and legitimate sources of information. And in so doing, I evolve as I give birth to new organs of perception. I am able to perceive, both inwardly and outwardly, a developing landscape of wholeness.

In my view, this is the entire point of a Goethean Plant Study and why I am so passionate about guiding this process with others who also desire to learn more about the plants, who strive to evolve as clinicians, as herbalists, and as human beings. Once we have arrived at the end of a Goethean Plant Study, we are no longer the same as when we began. As Goethe wrote, “Every new object, clearly seen, opens up a new organ of perception in us”.[xiv] It is in this way that the Goethean process teaches us a new way of seeing, perceiving, observing all phenomena, including ourselves.

Learning to Listen with Soft Eyes

Before describing the beautifully enriching Goethean plant study of White Pine, I want to elaborate upon a concept known as dyadic communication and how it is relevant to the Goethean way of studying plants. This is a concept that my dear friend and business partner Brooke Sackenheim has used to describe our plant-centered mission here at Sovereignty Herbs. It is a brilliant use of the term ‘dyadic’, and am grateful she has brought it to my attention. Let me explain…

I am often asked by students and herbal colleagues if the Goethean plant study process is about plant communication or learning how to communicate with plants. I answer this question by asking the questions: What do we mean exactly by plant communication? Do we mean that we talk to the plants and tell them things about ourselves? Or does it mean we ‘hear’ the plants speaking to us…providing us with never-before-told truths about ourselves and the world around us? About themselves and their medicine?

If the answer to these latter questions is yes, then I could accept one’s attempt to describe the Goethean way of studying plants as a means of communication. That is, if we define communication as an exchange of information. There is much information to be received through these plant studies; there is much to be observed and perceived through our patient gaze, attentive mind, and open heart.

However, when I think of term ‘communication’, I am torn between the concepts of dialogue and diatribe. In this way, the Goethean plant study process is less about plant communication and more about learning how to ‘listen’.

For example, I often tell my students that they must forget everything they think they know about the plant we are studying…at least while the study process is taking place. I even ask them not to call the plant by its human-given name, English or otherwise. For even in that second, when we give a plant a name, a label, we inevitably stop listening. "You are white pine, and you are this and you are that, and I can use you for this or that..."...and it just. keeps. going. A regurgitation of ‘facts’ filed away in the brain's archive of 'know it all-ness'. The place of ego and shadow, comparison and projection.

In actuality we know nothing at all, nor have we learned anything at all in this interaction. We have merely recited some concept of 'knowledge' which in many cases only involves projecting ourselves onto the plant, often with a sense of pride for our knowingness. This type of interaction is a one-way conversation that is not about seeking knowledge; it is about seeking our reflection. Simply put, in this interaction we have done all of the talking and none of the listening (think about someone you know that never quite shuts up nor provides space for you to express your truths – yes, husband, I know).

And by 'listening' I do not necessarily mean waiting patiently for some verdant voice to enter into your consciousness, any more than I mean to infer some psychic, shamanic, or magikal process (not that the psychic, shamanic, or magikal aren’t relevant and important for many in regards to the interactions with kingdom Plantae). What I do mean, is learning to cultivate one's senses of perception, like Goethe’s process asks of us; to take in the details of the phenomenon and leave our knowingness out of it. In acknowledging these tendencies Goethe wrote,

“We must renounce these and as quasi-divine beings seek and examine what is and not what pleases…Just as the sun coaxes forth and shines on all plants, botanists should consider all plants with an even and quiet gaze and take the measure for knowledge – the data that form the basis for judgement – not out of themselves but out of the circle of what they observe.”[xv]

This is where the concept of dyadic communication comes in (thank you Brooke!). In the narrow sense of the term, it refers to any communication between two individuals (for our purposes we are defining communication as the exchange of information and two individuals as human and plant). More broadly, the concept of dyadic communication acknowledges that with most interactions there are assumptions and preconceived perceptions (interpersonal perceptions) that are brought to the table and it is precisely these assumptions and preconceptions that may result in our talking at another, rather than communicating with another.[xvi]

In the end, I always strive to participate in Goethean plant studies with the awareness that the process is not as much about Self as it is about selflessness. It is not about some end result, it is about staying present in the resplendent moment. It is not about how much I already know, but all that there is still to observe. It’s about learning to perceive the wholeness of a phenomenon with an ‘even and quiet gaze’. It’s about learning to listen with soft eyes.

A Goethean Plant Study Takes Place in Stages

The very act of meeting another being on such a deep level is often a shocking experience; often something akin to falling in love. One can never forget it. - Margaret Colquhoun, Schumacher College, 2003

Raindrops on White Pine (Pinus strobus) needles. Photo: Erika Galentin

Just like chapters in a novel or acts in play, the Goethean plant study takes place in stages with each stage grounding the next as the gesture or expression of a plant unfolds. These stages, or modes of perception, vary a bit between those of us practicing and teaching the Goethean way of seeing depending on the context to which we are applying this process.[xvii] Their implementation and interpretation may also vary. The recent White Pine study, which I am about to present, encompasses the approach of my teacher, the late Margaret Colquhoun and elements that were invoked during my studies at the Scottish School of Herbal Medicine. Indeed, for better or for worse, I have also added a bit of my own personal approach.

There are four main stages presented here, as in line with my training and tradition, with an addition of the initial intuitive encounter, or meeting of the plant, as a preparatory phase. Presenting and guiding a Goethean plant study in this way can come across as having quite rigidly and sharply delineated sequential processes, when they are indeed meant to flow, like water through its banks, from one mode of perception to the next as the expression of the plant, or its wholeness, is perceived. Isis Brook explains this well when she writes,

“In teaching the perceptual modes are distinguished more sharply than when used by experienced practitioners. Beginning to separate these different perceptual modes and to experience their qualities is a large part of what is distinctive about the Goethean approach. Once the observer can experience these processes consciously, they can flow into one another in a less structured way.”[xviii]

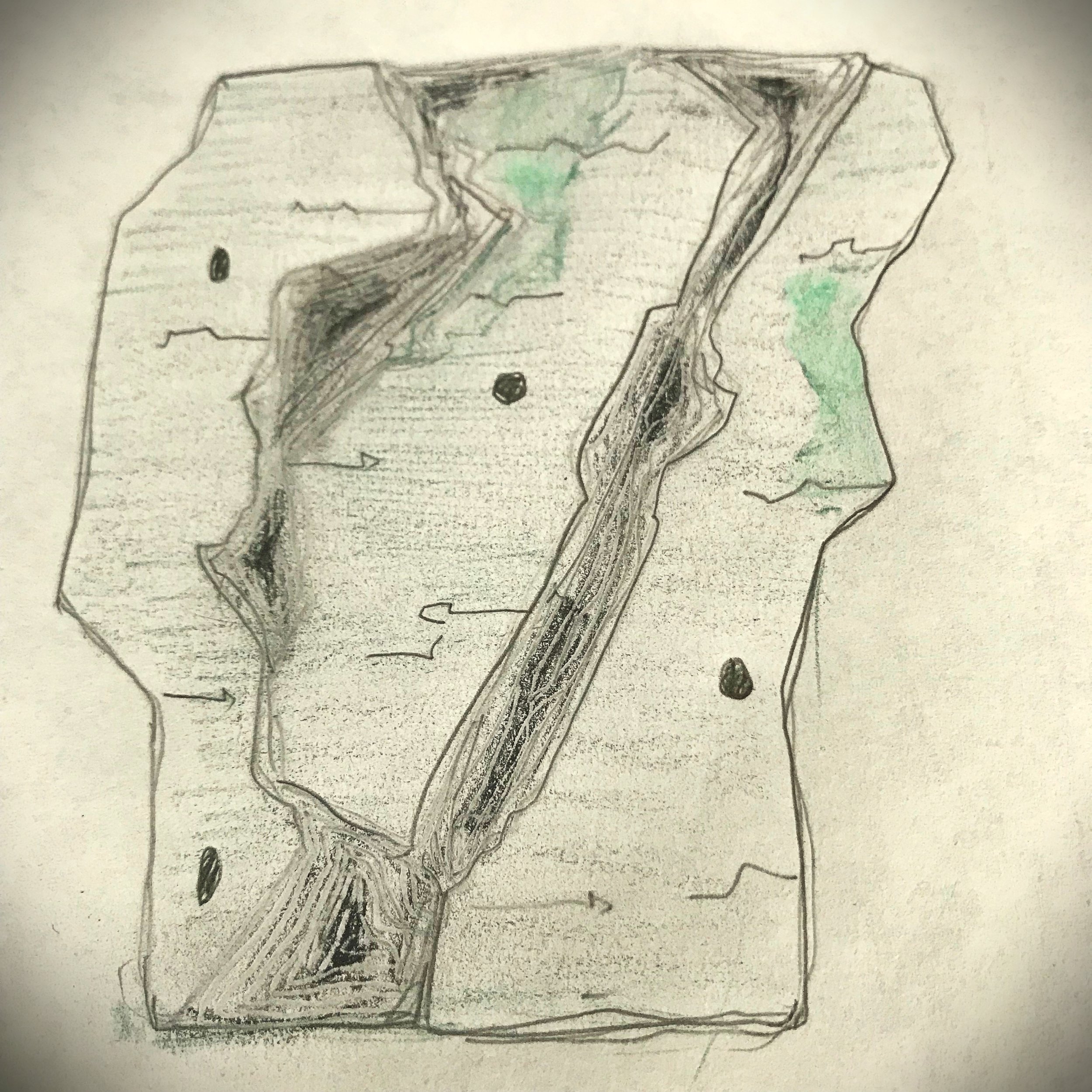

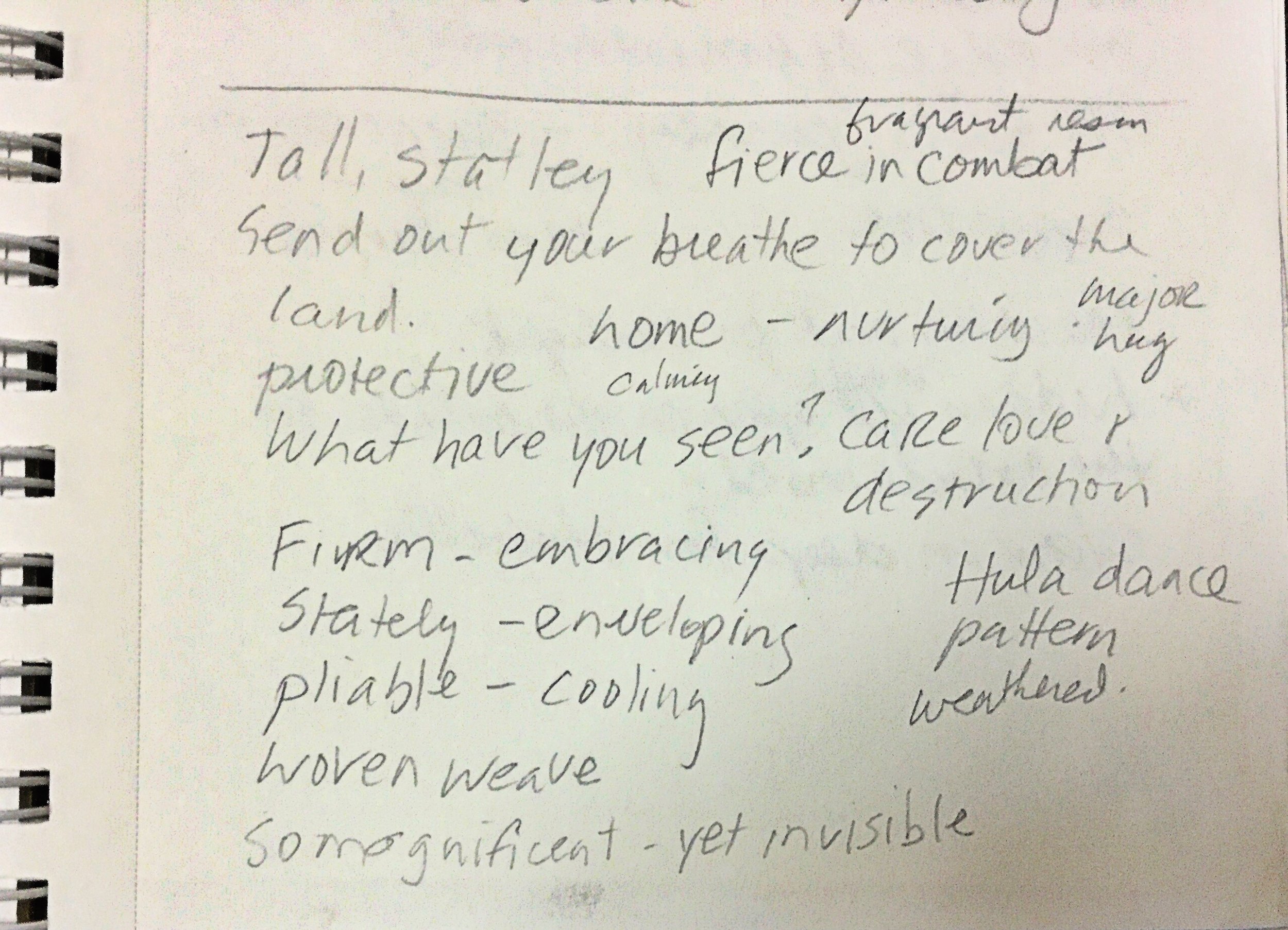

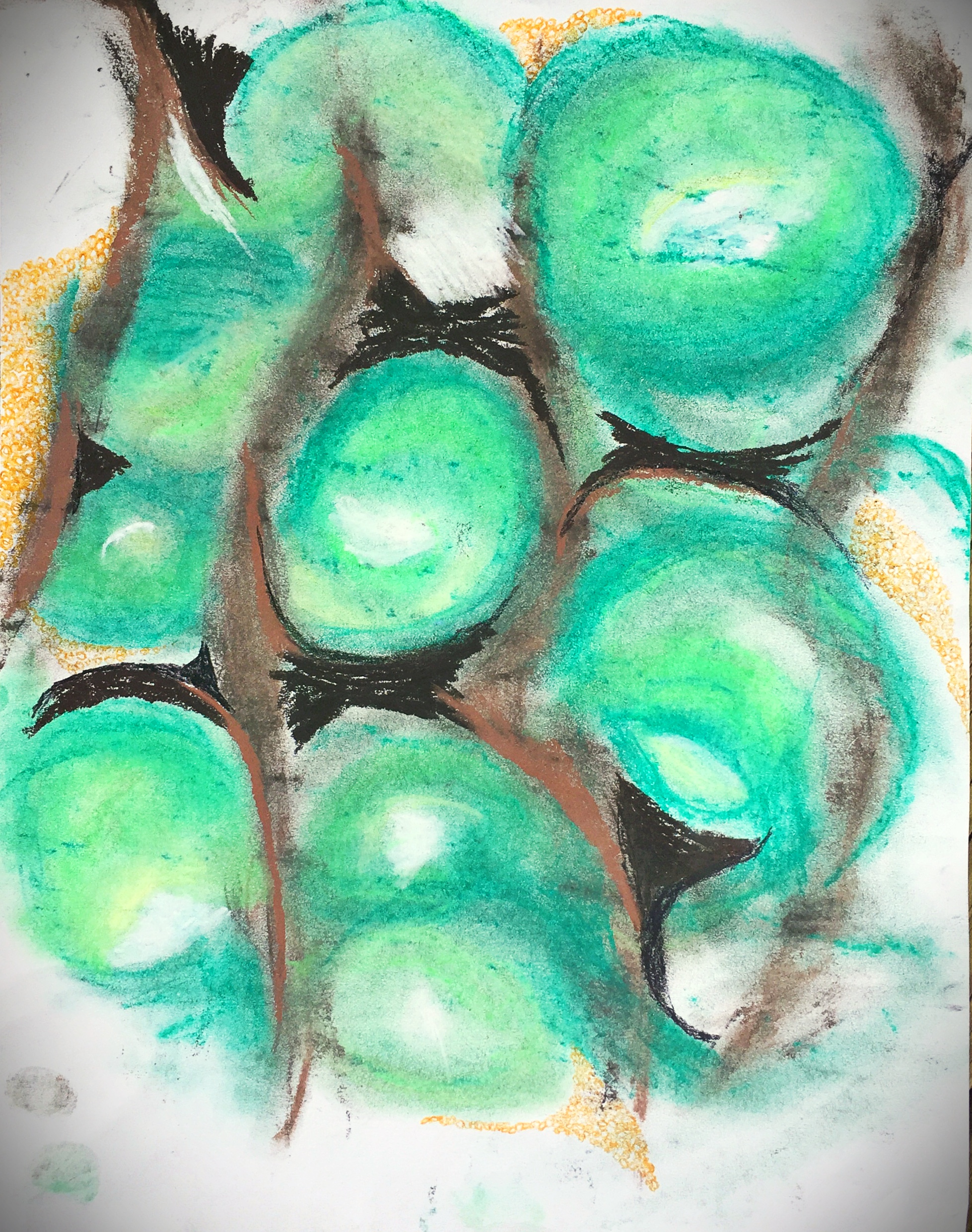

In most cases, as is in this case of White Pine, different mediums are used to document our perceptions and observations, the most common being written word and drawing, painting, or sketching. Sometimes the plant itself is used (this will become clear momentarily). I have also begun to incorporate photography (for those of you who know me also know how much I love working with the plants in this way). When I am asked to guide a Goethean Plant Study, I ask fellow participants to bring whatever mediums they desire to use, while I also provide an array of colored pencils, pastels, sometimes water colors. I also ask that they bring blank, unlined paper (for in my experience, lines on a page invite preconceptions that are undesirable to this process).

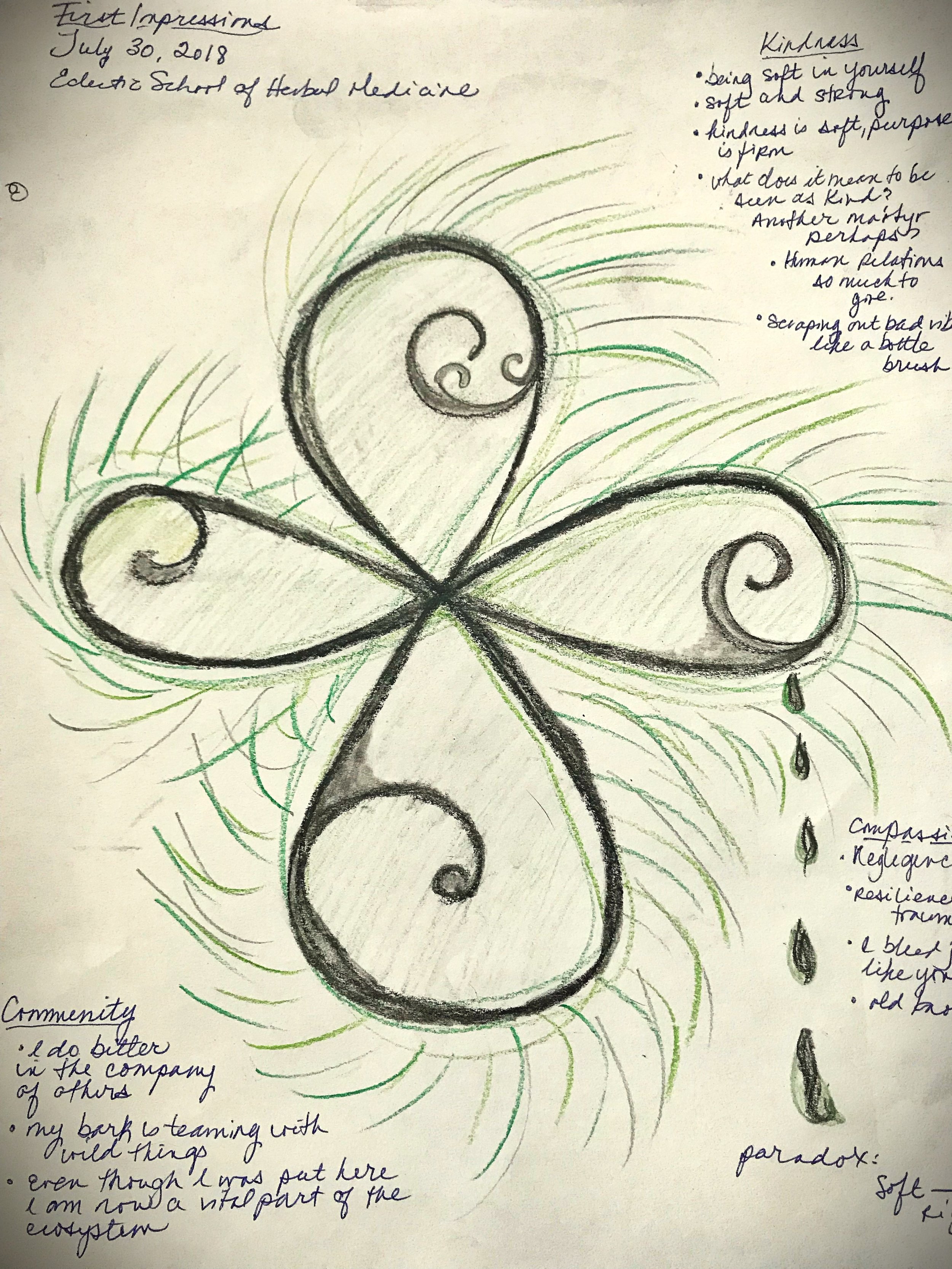

Preparation: Meeting the Plant & First Impressions

First Impressions. Eclectic School of Herbal Medicine, July 2018. Photo: Erika Galentin

Some Goethean guides don’t actually consider this initial intuitive meeting a ‘stage’, any more than a ‘warm-up’ would be considered an actual part of a work-out. This is meant to be an exercise in preparation, becoming present with the plant that is going to be observed. It gives space for us to be who we usually are in this world, to approach the plant and have feelings, to have likes and dislikes, to engage with our human intuition.[xix] It allows for us as observers to acknowledge and recognize our preconceptions, memories, and knowingness about the plant. As I remember my teacher Margaret Colquhoun explaining it, this preparatory phase is about opening our hearts to the plant and developing a ‘sense of feeling’ for it. It is about developing our hearts as organs of perception. In essence, it gives study participants an opportunity to indulge in ‘Self’, to get ‘Self’ off their chests (so to speak), lest they be able to set ‘Self’ aside for the subsequent progression of the study.

As I was taught at the Scottish School of Herbal Medicine, we gather in a single file line and without speaking take a slow walk to meet the plant of our study. We are focusing on the sounds and scents of the breeze, notes of the songs of birds and insects, and in our case experiencing the sensation of summer raindrops against one’s skin. This meditative walking brings us into the present moment and prepares us for this first encounter. In this manner, we travel to several different locations so we can meet the plant in a variety of growing conditions and microenvironments. Each location is granted the space for intuitive interpretation.

Walking to meet the plant. Eclectic School of Herbal Medicine, July 2018. Photo: Suthi Nagar @ladynagar

In the Goethean plant studies that I guide, all aspects of this preparatory phase are documented with both written word and drawing or sketching. However, I ask fellow participants to not share these first impressions with anyone…at least not in these initial moments. We keep them to ourselves, or between the Self and the plant, until the end of the study when we are bringing all of the elements of our experience together. At this time I also remind students not to call the plant by its human-given name but rather refer to it as ‘the phenomenon’ or simply ‘the plant’. It is too early in the study to be utilizing distracting labels.

In keeping with my Goethean process, I will wait to share with you, dear reader, some of our first impressions until the end of this here journey. I will indulge your curiosity however, by asking for you to take note of yours:

Meeting the plant. Eclectic School of Herbal Medicine, July 2018. Photo: Suthi Nagar

Stage One: Exact Sensory Perception

Perceiving physical facts. Eclectic School of Herbal Medicine, July 2018. Photo: Erika Galentin

I explain this first stage of the plant study to fellow participants as describing the plant and everything we see about the plant, all the botanical, environmental, and ecological details we observe…ad nauseam. We are to refrain from using language such as ‘it looks like (enter noun here)’. We are exercising our abilities to come up with unique and specific language that describes, exactly, our sensory perceptions. This is actually much harder to do than it sounds.

This first stage of the study is when we stand back from our previous preparatory personal encounter with the plant. We step outside of our intuition and approach the plant more objectively, without judgement or evaluation, without making assumptions or concocting theories about why things are, but simply noting that they are present. This is developing the skills of Goethe’s ‘theory-free’ observation. As Brook writes,

“Our theories and feelings about things must be held back in order to let the facts speak for themselves.” [xx]

In a nutshell, we are taking in and documenting all of the physical facts of the organism and in doing so preparing a solid ground from which subsequent modes of perception can unfold.

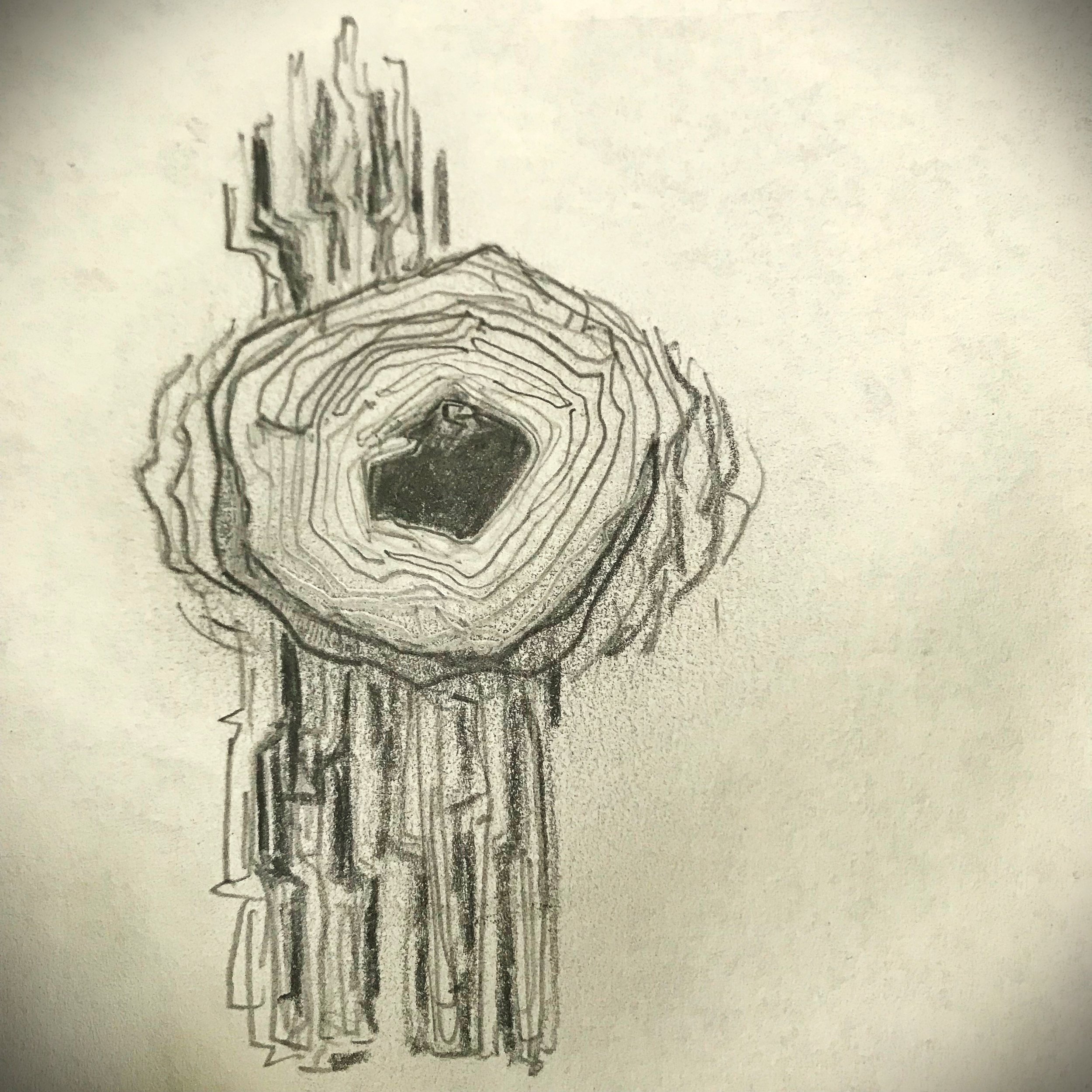

We take turns reciting the physical facts we encounter, making sure that each participant’s attention is drawn to that specific feature. I ask participants to write down a few physical facts that have sparked in them, in some way, a sense of curiosity, of wanting to know more. We then sit and draw what we see, whatever detail we choose, however large or small.

We are now rooted and ready to proceed through to the next mode of perception...

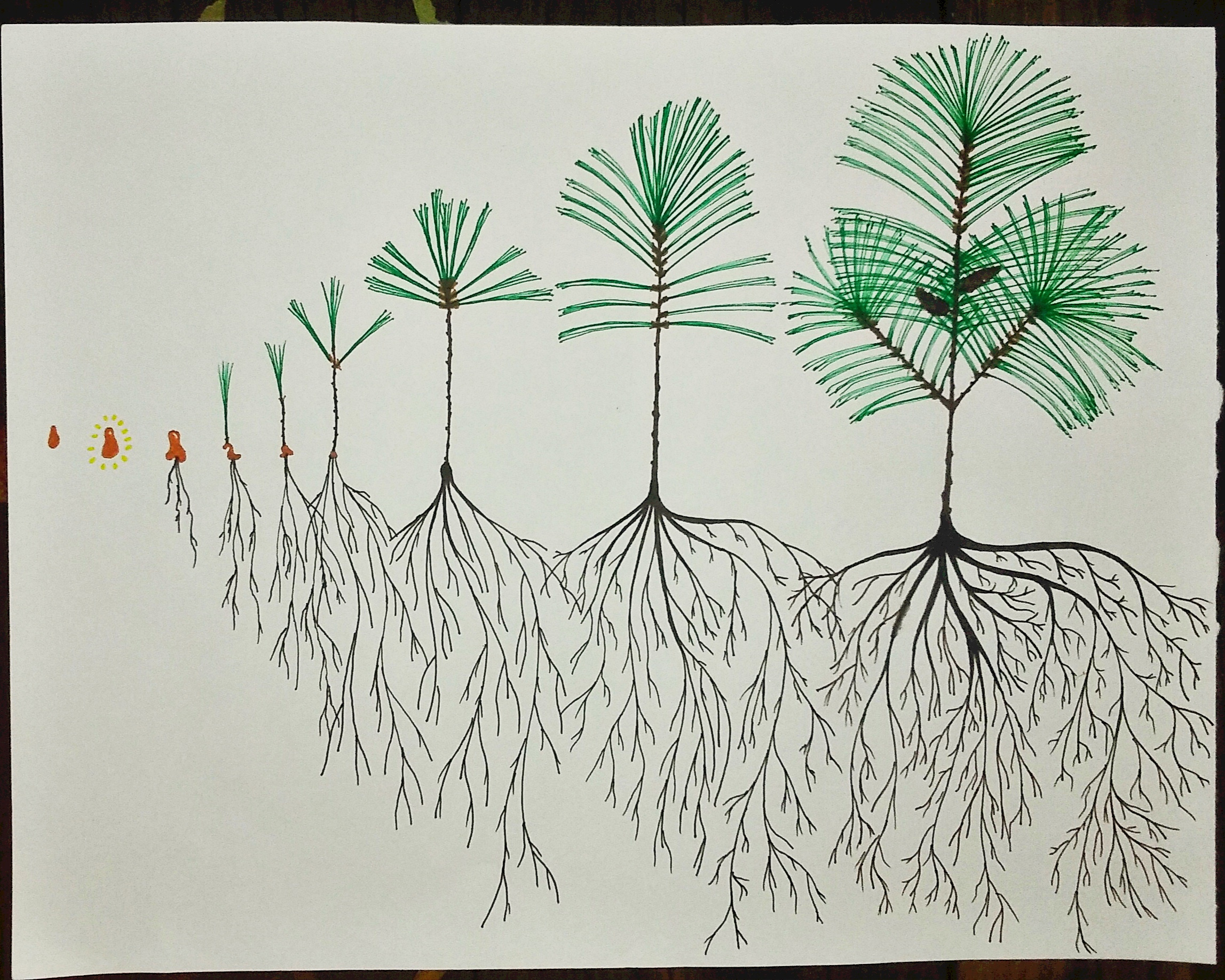

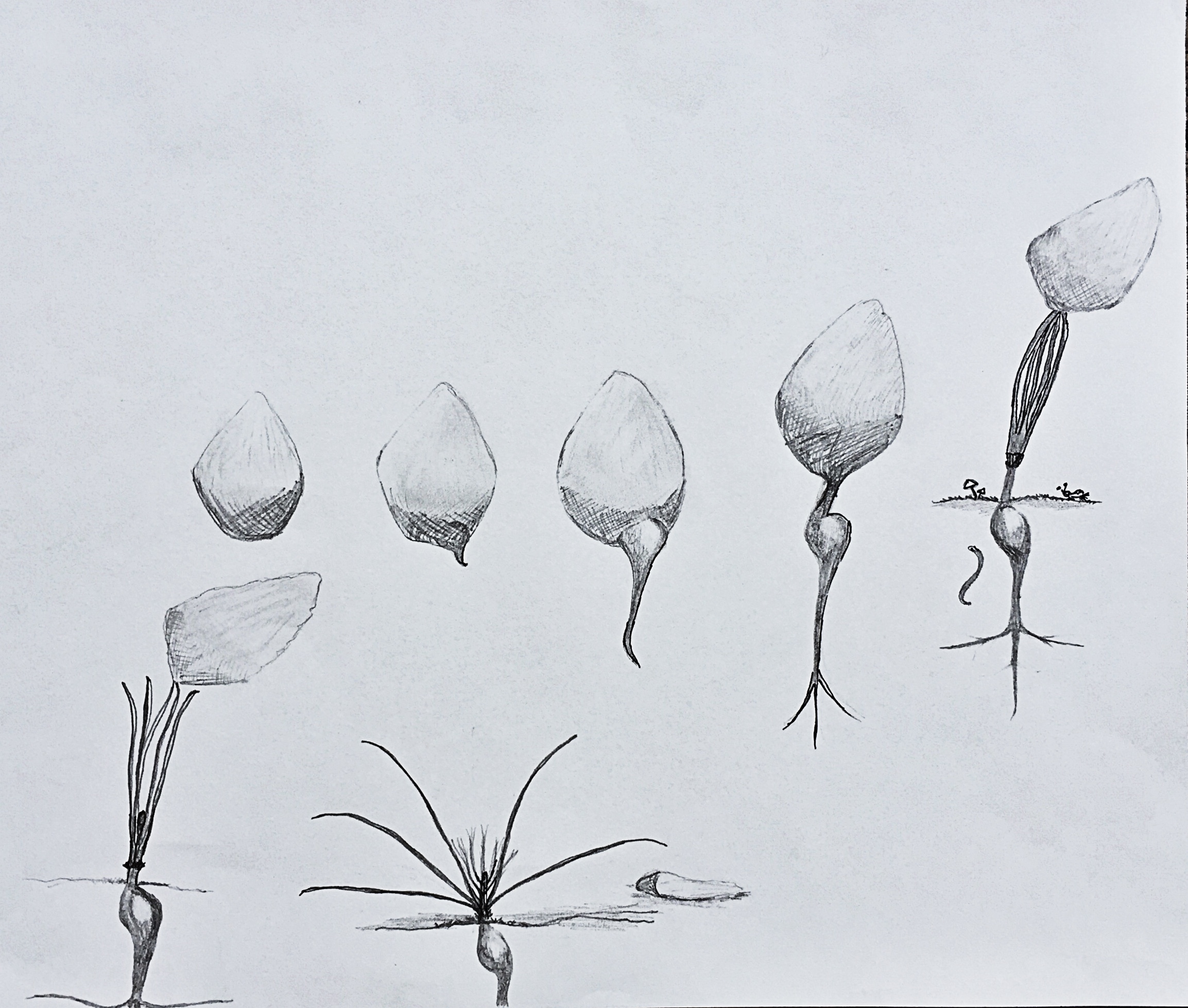

Stage Two: Exact Sensorial Imagination - Flowing through Time

When we encounter a phenomenon in a single moment in time, we are only observing a snapshot of that phenomenon. In the case of a plant, going both backward and forward through time the plant changes its form, its habits, its chemistry. What begins as a seedling, was once a seed, and before that an ovule within a flower or naked, wedged between the scales of the pine cone. Moving forward in time, that ovule is fertilized and undergoes a series of physical and chemical changes in becoming a ripened seed. This seed then finds fertile ground, and imbibed with water, swells and germinates. Very soon a primordial root, the radicle, will emerge and begin the journey into the earth as a developing root system. And if an angiosperm, soon after that the cotyledons will unfurl and sprout towards the sky leading the way for the first set of true leaves. The stem broadens and elongates, and more leaves emerge. Perhaps they grow opposite to each other; perhaps they alternate up the stem. And then, in its continued expression, branching begins; reaching, stretching, more leaves, more branches…until a leaf, still enclosed within the passage of time, is chosen to develop even further into a flower. And thus, the cycle continues.

When reading the previous paragraph were you imagining, with your mind’s eye, the processes being described? If yes, than you were engaging with your sensorial imagination as a mode of perception. You were also engaging with revolutionary concepts Goethe described in his Metamorphosis of Plants. Although the notion of metamorphosis had already been explored and applied to other life forms, Goethe was the first in his time to apply this concept to plants.[xxi] In fact, he coined the term ‘morphology’, the study of the forms of things, wielding it into a scientific discipline which still holds its own within the modern study of botany.[xxii]

Goethe's carnation: “Seeing no way to preserve this marvelous form, I attempted an exact drawing of it, whereby I deepened my insight into the fundamental concept of metamorphosis.” — Goethe Source: Journal of Natural Science Illustration

Stage two of the plant study offers us the opportunity to use our imagination, or sense of fantasy, to perceive the development of the plant either forward or backward through time and in so doing, perceive the essence or expression of the plant as a whole being. We are moving beyond an objective mode of perception, beyond a frozen moment, to experience the plant’s dynamism. We are seeking to observe its expression as the path to observing its wholeness.

The difference between stage one and stage two could be likened to the difference between examining a photograph of an infant’s face, noting every physical detail (exact sensory perception), and using the details from that photograph to imagine that infant becoming a toddler, an adolescent, then an adult, then an elder. How do the details of their expression evolve through time? If the photograph is of an elder, how would the details of their expression manifest as a younger version of themselves, as a young adult? An adolescent? A child? An infant?

Every detail observed in our physical fact finding mode of perception (stage one) developed from a previous detail, and will continue to develop through time into something else. However, we must not let our imaginations run wild…there are patterns within which are held the parameters of a plant’s expression. As Brook writes,

“The second stage could be seen as a training of the imaginative faculty in two directions: firstly to free up the imagination and then to constrain it within the realms of what is possible for the phenomenon being studied.”[xxiii]

She also warns us of a common pitfall in this second stage,

“The difficult part of this way of seeing is to bring to awareness these flowing processes in the plant without freezing them with the solid nature of the exact sense perception. The aim is not to use the static recognitions of the first stage, but rather, to take those solid objective qualities into the new realm of movement and allow them to flow into one another.”[xxiv]

There are a variety of exercises that can be used to encourage this imaginative mode of perception, or what Goethe referred to as exakie sinnliche phantasie. One of the most common mediums I use is choosing a physical fact observed from the previous stage and drawing its development either forward or backward through time. In many cases I will also harvest portions of the plant so that we can put them together, like pieces of a puzzle, to not only capture the development of the plant, or one of its features, through time but to also begin to understand what Henri Bortoft referred to as ‘seeing the whole within each of the parts’ or ‘multiplicity in unity’.[xxv]

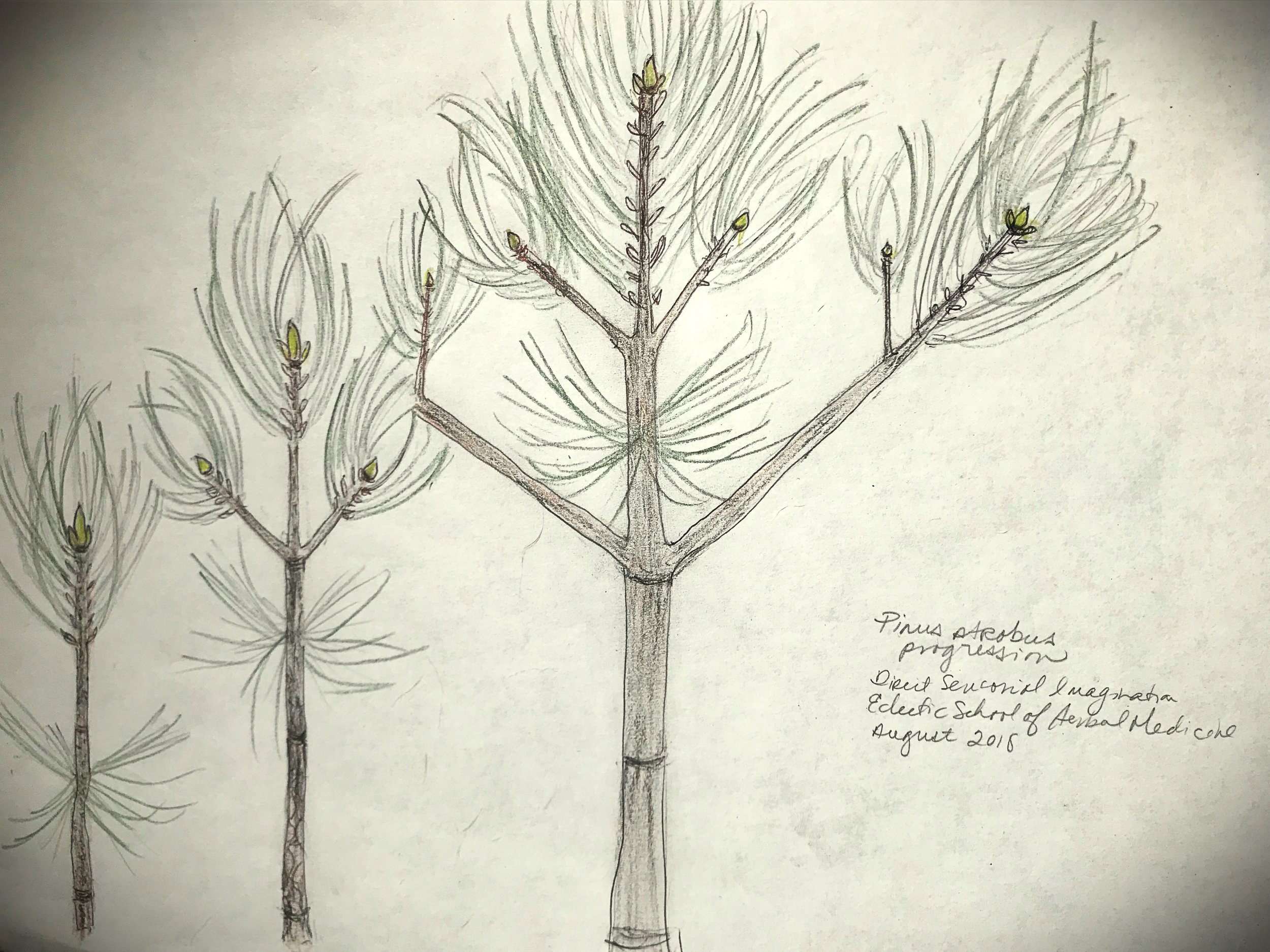

For this white pine study, we reconstructed the development of the plant through time using features from a harvested branch and pine cones we collected from the ground. We also chose to draw progressions of a physical fact either forwards or backwards through time.

Stage Three: Seeing in Beholding - Gesture & Expression

Eclectic School of Herbal Medicine, July 2018. Photo: Erika Galentin

As I write through these stages, they are becoming harder to explain, and perhaps exceedingly abstract without the context of having participated in them first hand. The only way that I can describe it is akin to describing an oscillation, or perhaps a tide, as we step back with the Self and then again step forward leaving Self behind. As Brook explains,

“To experience the being of a phenomenon requires a human gesture of ‘self-dissipation’. This effort is a holding back of our own activity—a form of receptive attentiveness that offers the phenomenon a chance to express its own gesture.”[xxvi]

This third stage has also been described as a distillation of the phenomenon, whereby observations obtained through the previous two modes of perception are deepened through uncovering yet another mode of perception.[xxvii] And it is in this newly uncovered mode of perception where the plant starts to take a more active role; where it encounters the observers rather than the other way around.[xxviii] As I remember Margaret Colquhoun putting it, in this mode of perception we have become primed to listen more intently to what the plant is trying to tell us about itself. It is where the plant begins to take on meaning in and of itself,[xxix] and where we are able to glimpse the essence of its being.

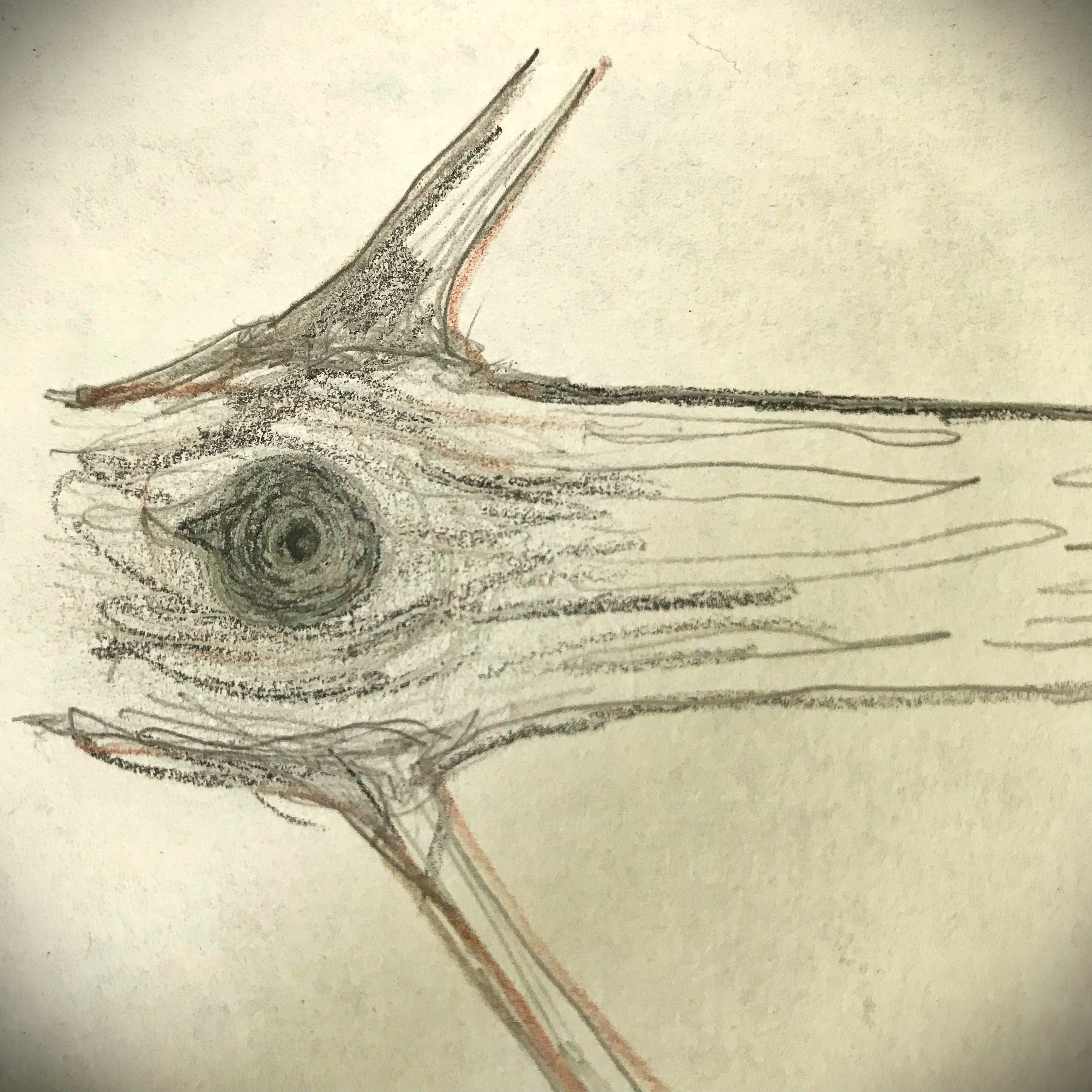

Seeing in beholding. Charcoal rubbing with eyes closed. - Erika

This mode of perception is often also referred to as inspirational or as an invitation for inspiration to enter our mode of perception.[xxx] It is often achieved through various artistic mediums for example poetry, interpretive dance, and of course, drawing, painting, or sketching. And it is in this stage where I was taught to bring in the art of medicine making as a means of receiving the gesture or expression of the plant…for the medicine of the plant and the ingestion thereof can provide a deep and profound opportunity to develop this mode of perception.

But before the making of the medicine, I asked the students to close their eyes and draw the plant, or an aspect of the plant without looking. By closing our eyes we can turn off the ego completely, and just like interpretive dance, experience the movement of the gesture of the plant through our own movements and gestures.

Seeing in Beholding. Drawing expression of the plant with eyes closed. - Erika

I then collected the needles and sap from the branch that was harvested and used during the previous stage of our study and gently warmed them in a covered pot. They simmered for 30 minutes or so before the translucent tea was portioned out in tea cups and passed around the circle for a tea-tasting exercise.

This tea-tasting process, the likes of which I was taught at the Scottish School of Herbal Medicine by Keith Robertson, FNIMH and the late Christopher Hedley, is usually done blind whereby participants are not given the name of the plant and are discouraged from attempting to identify it throughout the duration of the exercise. Much like the rest of the plant study, in these tea-tasting moments, we are to turn our ‘knowingness’ off so that we can ‘listen’ to the medicine; to its scents, its flavors, its actions, its movements in the body. In this vein, I had not disclosed to the group which particular aspect of the plant I had decocted. It could have been the bark or the cones as easily as it could have been needles. The following is brief glimpse at what was perceived from the tea as a medicinal preparation of the plant:

Smell: Citrus, Baked Apples, Sweet, Warm

Taste: Tart, Whole, Buttery, Sour

Feels: Both moist and Dry, Warming, Nourishing, Quietening, Round/Soft, Daze, Resinous coating, Numbing roof and sides of mouth, Opening sinuses, Lightheaded, Temples, Centering in chest

Vibes: Airy, Sparkler effect, Softens, Dreamy, Brings order to chaos

Person: Monkey mind, Sanguine, Anxious, Weight on chest, Needing to feel more in control

At this time we also began to discuss a variety of paradoxes, or opposites, that had been hinting themselves to us throughout the study. Our experiences with the tea-tasting also added to this list:

Moist --- Dry

Soft ---- Rigid

Chaos ---- Order

Dark ---- Light

Movement ---- Stillness

We are now seeing the expression of the plant differently than we have in previous stages of the study. It was illumining and full of ‘ah ha!’ moments, just as other Goethean scientists have experienced. As Wahl writes of this thirds stage,

“…the experience of the phenomenon revealing itself in one’s own consciousness feels very much like a sudden flash of insight, much more like something received than something created.”[xxxi]

And Brook writes,

“It is exhilarating, as what comes can seem so foreign to oneself that it feels given and as if from nowhere.”[xxxii]

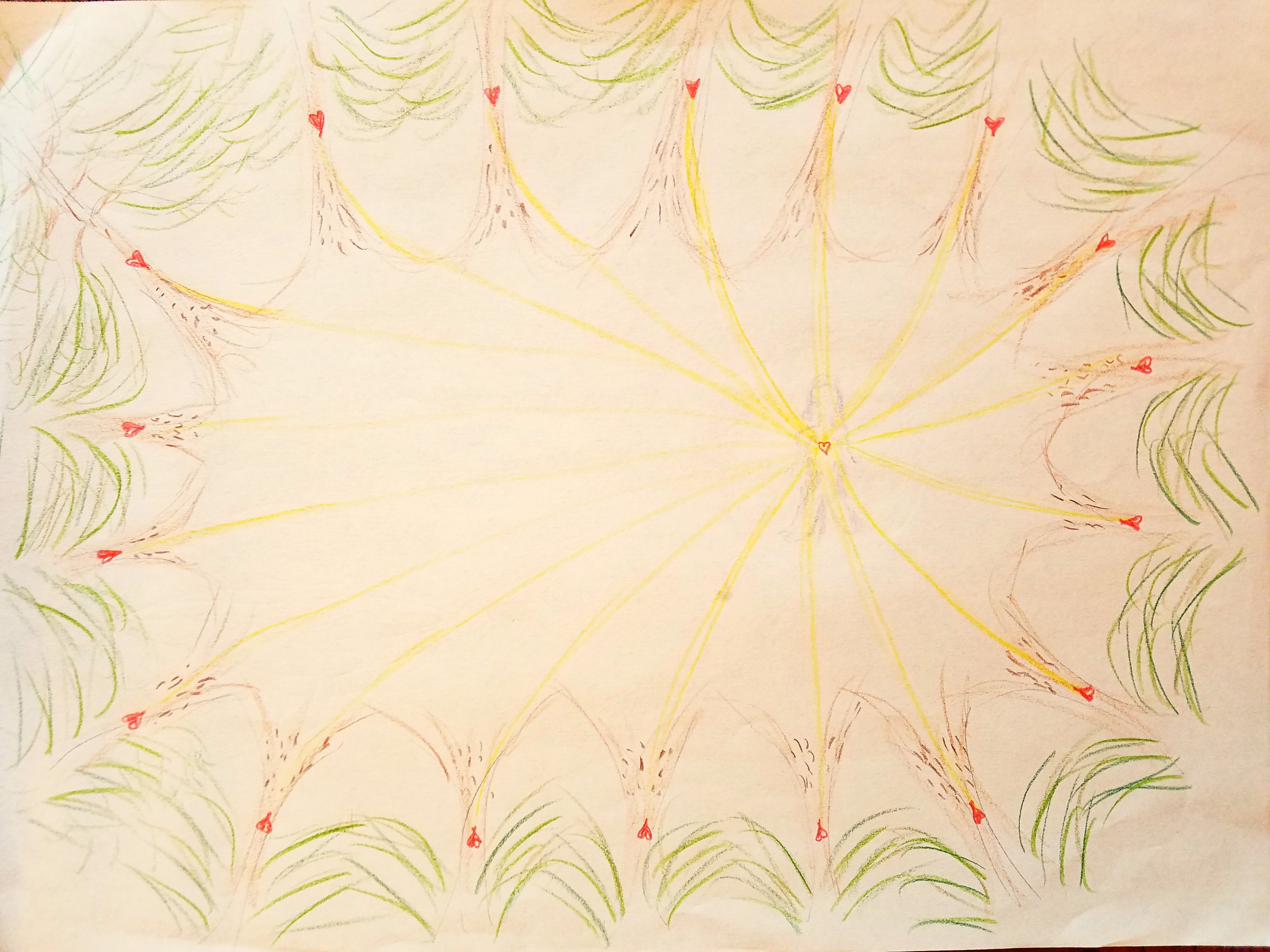

Stage Four: Bringing it all Together & Becoming One with the Essence

Bringing together elements of all previous modes of perception. - Ash

After our tea-tasting I described for the students what needed to take place the following day, for our final day of the study. At this time I normally ask fellow participants to find three facts about the plant from outside sources to share with the group during our final meeting. These facts could be about the plant’s biology or ecology, about its current or historical medicinal use, or about its folklore. They will be shared with the group, along with each participant’s perceptions and observations from each stage of the study, including, and sometimes most importantly, their first impressions from their first intuitive meeting of the plant...

I have also begun to incorporate distillation into the last day of the study. Not so much as an artistic act of making medicine like we did in the previous stage, but rather as a symbolic act, as we distill our observations into this final mode of perception. In addition, one of my teachers of AromaGnosis, Florian Birkmayer, MD, refers to the aromatic molecules captured through the distillation process as molecules of communication or molecules of connection. He speaks of them as the soul of the plant, and in many ways observing the soul of the being is very much what this final stage of the plant study is about; encountering what Goethe referred to as the ‘pure phenomenon’ or ‘archetype’ of the organism.[xxxiii] As aromatic distillation is capable of transmitting potent, pregnant meaning, it seems as natural a process within a plant study as it does a necessary one…

Collecting water from the creek to fill the copper still. Eclectic School of Herbal Medicine, July 2018. Photo: Erika Galentin

Thus, with a variety of pruners and scissors in hand we broke off into different directions to harvest and collect material from the plant to place into the copper still for the following day’s aromatic distillation. Needles, shorts of branches, pieces of bark, sap, and cones were collected an added to the still. We then walked our bounty to the creek and filled it to the brim with the mountain’s sweet water. The material was to sit overnight in the copper belly of the still, initiating the archetype’s slow and gentle release.

While the distillation is taking place, the fire is burning, the water warming, we go around in a circle, each sharing our words, our thoughts, and our drawings. They are placed on the floor in the middle of the circle for the group to see. We describe what we have observed in each of the stages. We share the facts that we have found about the plant from outside sources. This is also when we finally share our first impressions from our initial intuitive encounter with the plant. We make connections between each other’s observations. We make connections within ourselves. As my teacher Margaret Colquhoun once said of this process,

“Here, on a rather more conscious level than that previously experienced on our journey of discovery, we awaken to something in both the plant and in ourselves, which has a ringing correspondence within us.”[xxxiv]

Bringing it all together. Eclectic School of Herbal Medicine, July 2018. Photo: Erika Galentin

As the distillation progresses, as we gently ask the ‘soul’ of the plant to reveal itself, it is welcomed by each participants' awakening to it and it is beholden to their newly developed organs of perception.

Once we have shared our observations with one another, the distillation is complete. We pass the hydrosol around the circle taking note of its aroma and the images, feelings, intuitions, psychic changes that it brings forward in each of us. We relate these new observations to what we have just shared of our first impressions, sensory perceptions and imaginings, what we have already glimpsed as the essence or expression of the plant as a being.

And then we walk, silently and in a single file line, to a location that was enclosed within a ring of tall and broad white pine trees. We find a large spiral that has been traced into the soft dirt and stand around it in a grateful circle. We have brought the hydrosol with us, and once again we pass it around each tasting a drop, just a single drop, as we are moved into and through this final mode of perception; being one with the plant, becoming one with the essence. We are filled with a unique joy as each of us realize...‘now I am knowing’.[xxxv]

Erika is available to teach this process around the United States and abroad. If you are interested in learning more about hosting Erika for a Goethean Plant Study, please contact her office via phone (+001 740-229-9952 ) or by email: office@sovereigntyherbs.com

Footnotes

[i] Holdrege, C. 2014. Goethe and the evolution of science. In Context, 31, The Nature Institute. Retrieved from: http://natureinstitute.org/pub/ic/ic31/goethe.pdf

[ii] Bortoft, H. 2013. The Wholeness of Nature: Goethe’s Way of Science. Edinburgh, Scotland: Floris Books.

[iii] Ibid. Bortoft 2013 pg. 247

[iv] Ibid. Holdrege 2014 pg. 13

[v] Von Goethe, J.W. 1995. The Scientific Studies (D. Miller, Ed. & Transl). Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. pg. 203. As quoted in, Holdrege, C. 2014. Goethe and the evolution of science. In Context, 31, The Nature Institute. Retrieved from: http://natureinstitute.org/pub/ic/ic31/goethe.pdf

[vi] Von Goethe, J.W. 1823. The Experiment as Mediator of Object and Subject. Quoted text taken from the 2010 Translation by Craig Holdrege retrieved from: http://natureinstitute.org/pub/ic/ic24/ic24_goethe.pdf. Goethe wrote this essay in 1792, and it was published for the first time, in a slightly altered version, in 1823. Source of translation: “Der Versuch als Vermittler von Objekt und Subjekt,” in Goethe’s Werke, Hamburger Ausgabe, Bd. 13 (Munich: Verlag C. H. Beck, 2002, pp. 10-20).

[vii] Ibid. Holdrege 2014 pg. 21

[viii] Ibid. pg. 19

[ix] Ibid. pg. 19

[x] Ibid. Holdrege 2014 pg. 21

[xi] Ibid. Bortoft 2013 pg. 272

[xii] Brook, I. 1998. Goethean science as a way to read the landscape. Landscape Research, 23(1), 51-69.

[xiii] Irwin, T. n.d. Audit of Goethean process as outlined by leading experts in the field. Carnegie Mellon University. Retrieved from: https://goetheanscience.files.wordpress.com/2015/12/overview_audit_of_goethean_process-edu-libre.pdf

[xiv] Ibid. Holdrege 2014 pg. 20

[xv] Ibid. Goethe 1823 pg. 19

[xvi] Almore, M.G. 1979. Dyadic communication. The American Journal of Nursing, 79(6), 1076-1078.

[xvii] Ibid. Irwin.

[xviii] Ibid. Brook 1998 pg. 52

[xix] Ibid. pg. 53

[xx] Ibid. pg. 54

[xxi] Von Goethe, J.W. 2009. The metamorphosis of plants; Introduction and photography by Gordon L. Miller. Cambride, MA: MIT Press.

[xxii] Wahl, D. 2005. “Zarte Empirie”: Goethean Science as a Way of Knowing. Janus Head. Retrieved from: http://www.janushead.org/8-1/wahl.pdf

[xxiii] Ibid. Brook 1998 pg. 55

[xxiv] Ibid. pg. 55

[xxv] Ibid. Bortoft 2013 pg. 274

[xxvi] Ibid. Brook 1998 pg. 56

[xxvii] Hoffman, N. 1998. The unity of science and art: Goethean phenomenology as a new ecological discipline. In, Seamon, D., & Zajonc, A. (eds.). Goethe’s way of science: A phenomenology of nature. Albany, NY: SUNY Press.

[xxviii] Ibid. Wahl

[xxix] Ibid. Hoffmann

[xxx] Ibid. Brook

[xxxi] Ibid. Wahl pg. 64

[xxxii] Ibid. Brook pg. 56

[xxxiii] Ibid. Hoffman

[xxxiv] Colquhoun, M. 2003. Lectures at Schumacher College.

[xxxv] Holdrege, C. 2005. Doing Goethean science. Janus Head. Retrieved from: http://www.janushead.org/8-1/holdrege.pdf