“When the leaves have forsaken the trees, and the woods are chilly and desolate, there seems nothing to attract one to these bare sentinels of the forest, but Mother Nature has always something to offer to those who love her.” - Elizabeth H Kirkbride, “A Winters Walk”, February 1907 (1).

Winter. I’ve never much cared for the cold. The moisture from my hot breath is forming icicles on the scarf wrapped around my head as I persevere upslope. “It’s easy to scorn away the beauty of the world in such temperatures”, I say to myself, awaiting the warmth of an elevated heart rate and rushing circulation. Eyes wide open; I begin to recognize a color and movement in the winter woods that I have often ignored. The breeze is tickling the marcescent copper-colored leaves of the American Beech (Fagus grandifolia Ehrh.) (2). They are everywhere…speckling the slopes of this mixed mesophytic winterland (3), donating their brilliance and tenacity to an otherwise sleepy landscape. My mind is now deeply entranced with what is sparkling before my eyes…“Surely I have noticed you before?” I ask through labored breath.

It is what it is.

American Beech is known as Fagus grandifolia Ehrh. amongst today’s Latin name-calling folks (4), although historically it was referred to as Fagus ferruginea Dryand., or Fagus ferruginea var. caroliniana Loudon (5).

Once upon a time, North America celebrated three distinct ‘races’ (not species) of American Beech. These races, ‘gray”, “red”, and ‘white”, represented different biogeographical regions as well as hair-splitting differences in morphological characteristics (6). To further this concept, genetic research from 2001 found American Beech populations consisting of two genetically distinct clusters (7). So, some botanical authorities hold that Northern and Southern beeches vary, and have described the southern form as F grandifolia var. caroliniana, or Carolina beech (8). But before I totally lose your attention here, I will go on to quote a highly respected botanist and naturalist who clarified the topic of “American Beech varieties” for me with the following sentiment:

“When it comes to Fagus grandifolia, I've never personally taken it to the varietal level, nor have I ever worked or talked with anyone who does…As far as I care to take it, even at my more advanced level of botany: a beech is a beech, is a beech and so on and so forth.” (Andrew Lane Gibson, personal comm.)

So there you have it…American Beech is a noble and solitary species, the only one of its kind in the genus Fagus on North American soil. It is special that way. Thank you Andrew Lane Gibson, aka. the Buckeye Botanist, for simplifying the matter.

As I continue my trek up-slope, I am filled with a sensation somewhere between ignorance and epiphany. Looking over my shoulders as to not miss one moment of the copper-glittered forest, I pry myself open to a greater philosophical meaning: American Beech is the only species in its genus here in the United States, but yet it is so incredibly common (9). And then the voice of Henry Ward Beecher (June 24, 1813 – March 8, 1887) enters my consciousness reciting his famous optimism: “The art of being happy lies in the power of extracting happiness from common things.” (10) I giggle aloud…leave it to my brain to quote Beecher while admiring Beech trees.

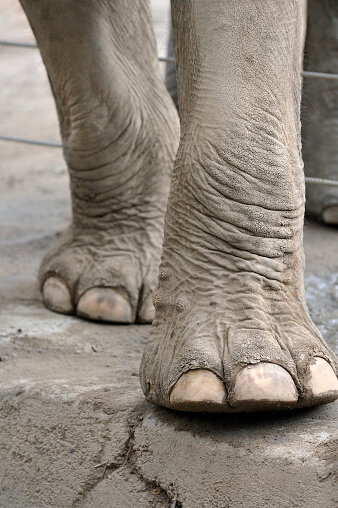

What do stiletto heels, a long-distance runner, and elephants have in common?

Still climbing, almost there. I can hear the whining laughter of black crows chasing away the Red Tail Hawk that has taken up residence in this long-forgotten hollow. I am on the hunt for the secrets of winter’s woods, preying upon opportunities to chase away the cold that so easily penetrates the heart and mind during this time of year. Today I have seized the occasion of American Beech, glowing steadfast against a somber background. And then I ask myself, “What do stiletto heels, a long-distance runner, and an elephant have in common?”

In any season the American Beech is most easily recognizable by virtue of its almost Casper white-gray bark and smooth complexion that glows in the woods amongst the darker faces of its neighbors (12). In winter, the eye-catching identifier is the golden-bronze, or copper-colored leaves that have remained attached to its branches, quivering in the slightest breeze. When they move they make a crackling sound, not unlike the burning of paper in a fireplace. When I look at the Beech I see many things, such as a sexy lady in stilettos (referring to the twigs and leaf buds) or the body of long-distance runner (the sinewy nature of its branches). I have often also likened the stout trunks of Beech trees to the appearance of the legs of elephants (at least this is how I am teaching my stepdaughter to recognize them). These trunks are smooth and unbroken, unless infected with Beech Bark Disease at which time the bark becomes pockmarked with blisters and cracks (13), not unlike the festering ulcers of human skin it is meant to remedy.

More often than not, one can also easily recognize a Beech tree from the various carvings, or ‘dendroglyphs’, that tattoo its tender and shallow surface. It is an American favorite in regards to professing love or claiming territory, and like R.W. Shufeldt (14) writes: “The majority of these [carvings] generally indicate that, in the spring the young man’s mind has a certain gentile inclination that ages ago became proverbial.” I am not so sure I could be wooed by such defacement, but to each one’s own.

A meal not to step on.

I can no longer sense the cold as I reach the ridge. Pausing for a moment, I am overcome by the ultimate awareness of accomplishment as I turn back around to admire the view that elevation has provided. I am maintaining a warm resistance to the sleeping world, a sensation that gifts me a reminder of how alive I really am. I crouch down to fix my bootlaces only to be met by the most curious yet unfriendly looking object begging not to be stepped on.

Ahh, the Beechnut. Long believed to actually be an ingredient of Beechnut™ gum (I can assure it was not). The American beechnuts are said to be one of the sweetest and most delicious of our native forests (16). But before I go further I must relate to you that there is a significant difference reported between the edibility of American Beechnuts and European Beechnuts (Fagus sylvatica). The latter has been described as unpopular in regards to human consumption, only being eaten when dictated by extreme famine (17). In fact, both American and European beechnuts are full of nutrition, being dominated by fats and fat soluble vitamins, protein, and starch (18). However, the European beechnuts have much higher levels of saponins and alkamides, phytochemicals that can cause headaches and abdominal symptoms such as cramping pain, profuse vomiting, and explosive diarrhea (19). In fact, the over indulgence of Beechnuts (unclear as to American or European) has even been blamed as the culprit in messy and uncomfortable deaths (20). Nonetheless, it has been recommended that beechnuts, American or otherwise, be roasted or cooked before consumption as the heat nullifies the substances which are thought to induce such dubious results (19). However, where there is poison there is also medicine. For example, one of the most popular uses for raw American Beechnuts among the Cherokee people was not as a food source, but rather as an anthelmintic (a substance that destroys parasitic worms) (21). This makes sense in regards to the phytochemistry of saponins and alkamides and their pharmacological action within the human digestive system (22).

There are many other delights to the American Beechnut, beyond being nutritious and more agreeable than their European version. They were once considered a delicious (albeit tedious) source of culinary oil comparable in flavor to olive oil, and were collected and used as such by the European settlers who no doubt had carried the tradition with them from the Continent (17). However, long before the settlers arrived here in the United States, this nutmeat oil was employed by the False Face Societies of the Iroquois as an ingredient in the medicinal mush of their healing ceremonies, although I could not track down why (23). The Iroquois also crushed and boiled fresh beechnuts to make a nutritious beverage (note it reads ‘boiled’, which implies ‘cooked’) (24). However, the medicinal virtues of American Beech do not stop at the mast...

More than meets the eye.

The historical use and therapeutic employment of medicinal plants in American medicine can be seen as the confluence of British, European and Native American knowledge and experience. As inferred above, the Iroquois appear to have had the most developed relationship with the species out of all other Native American tribes where an ethnobotanical record is present (25). The Iroquois revered both the leaves and the bark of American Beech as blood medicine (referring to its ability to ‘cleanse’ the blood) as well as an astringent (or drying) tonic to the respiratory system when employed in ‘wet’ conditions of the lungs like pneumonia or tuberculosis (26).

British and European knowledge contribute to the use of American Beech in American medicine perhaps as a result of the use of European Beech (Fagus sylvatica) in European medicine. European Beech has its own medicinal history that was most definitely carried ‘across the pond’ during the colonial period and projected onto its cousin, the American Beech (27). The clearest picture of the historical medicinal use of European Beech comes from the famous writings of Nicholas Culpeper (1616-1654) (28,29). He writes of the leaves as being governed by the influence of Saturn, and therefore cooling and binding in their nature (medical astrology used a fascinating classification system for the plethora of diseases and remedies of that age). He goes on to indicate the species use to relieve hot swellings and running tetters (29, 30). In addition to the medicinal virtues of the leaves, there is also a history of using the tar made from European Beech wood for various and sundry skin afflictions, most notably weeping eczema (31), as well as internally as a stimulating expectorant in chronic bronchitis (32). But more on tar later…

This is where we arrive at the conclusions of the American Eclectic and Physiomedicalist traditions of medicine which contain, in part, an amalgamation of Native American and European knowledge in regards to the therapeutic nature of American Beech and its various parts (33). The American Eclectic Materia Medica claims astringent (drying), tonic, and antiseptic properties of the bark and leaves stating their efficacy in treating dysentery, diarrhea, indigestion (perhaps from ulcers?), and low-grade fevers internally, as well as foul ulcers, frostbite, and burns of the skin (34). In addition to this, we have the Physiomedicalist application of American Beech in cases of atony of the urinary system (35). These indications and employments of American Beech match those of both Native American traditions and the European tradition. There is an agreement as to the cooling, drying, and toning nature of both the bark and the leaves, being applicable to a number of internal and external conditions as defined by hot, wet, and atonic manifestations. However, we are cautioned by the Physiomedicalist approach which states that there are more appropriate medicines that should be employed when these types of conditions are deep-seated and mortifying in nature (35). American beech is good at the mild, tonic stuff.

Based on this collective knowledge, American Beech appears to have an affinity for the respiratory, integumentary, and digestive systems (although I must say that I have never used this species in clinical practice, nor do I know of anyone who has). But believe it or not, it is highly likely that you have relied upon the American Beech in times of sickness without even knowing it. However, in order to convince you of this I must first tell you a story. Bear with me, this is where things get really interesting.

My dear patient, would you please swallow this tar?

Let me take you back a step and remind you about use of Beech Tar in Europe as a stimulating expectorant for chronic bronchitis (32). I followed this beech tar tradition through my research within American medicine and found John King’s 1854 The American Eclectic Dispensary speaking of ‘a peculiar substance obtained from tar’ (36). It turns out this ‘peculiar substance’ is creosote…yes that’s right, creosote. Many of us are familiar with the smell of railroad ties or telephone poles on a hot day? That smell is creosote, well at least the coal-tar variety.

You see, there are two main types of creosote produced; the stronger, more toxic, and highly carcinogenic coal-tar variety (which is predominantly used in the preservation of wood), and the less toxic wood-tar variety which was traditionally employed for medicinal purposes as an expectorant, anti-septic and anesthetic as well as in the preservation of meat (37,38). Creosote derived from the wood of American Beech was considered the best for medicinal purposes because it distills with higher proportions of guaiacol and creosol, two plant phenolics which are considered the ‘active’ medicinal ingredients (39,40).

Beechwood creosote (CAS #:8021-39-4) has been used as a disinfectant, a laxative, and a cough treatment. In the past, treatments for leprosy, pneumonia, and tuberculosis also involved eating, drinking, or inhaling beechwood creosote (yum!). It is rarely used for this purpose today, and is no longer produced in the United States (41). However, back in the 1940’s a Canadian chemist by the name of Eldon Boyd experimented with guaiacol and from it derived the substance glycerol guaiacolate, now more commonly known as Guaifenesin (42). He discovered that Guaifenesin increased secretions in the respiratory system and this substance is now a component of the modern over-the-counter cough remedies Mucinex, Robitussin DAC, Cheratussin DAC, Robitussin AC, Cheratussin AC, Benylin, DayQuil Mucous Control, Meltus, and Bidex 400 (42).

Ahem…let me clear my throat.

There is medicine in the moment.

The deathly quiet chill of winter is no match for me today, as the act of observation has been warming in nature, like a hearth fire for the soul. The American Beech is trying to teach me that its medicinal virtues go way beyond the phytochemistry of its mast, bark, or leaves. As if there is medicine in the moment of appreciation itself.

Let me explain…

As a medical herbalist I am always on the search for these types of ‘moments’. When a connection to a medicinal plant species takes on a form other than a capsule, tea, or extract. Don’t get me wrong here, my feet are firmly planted in the ground of scientific inquiry, but my definition of ‘medicine’ goes beyond the act of consuming therapeutic matter. To me, medicine is also about changing patterns. Patterns of behavior, patterns of emotional response, patterns of belief. Medicine comes in many forms. In this particular case, I am no longer the grumpy, unforgiving human that I was when I took off on this journey today. My attitude has changed, quantifiably so. And yes, yes…I should thank the increased blood flow, endorphins, and other biochemical ‘tailgate parties’ going on in my body due to the exercise (43). But today I will also thank the American Beech. It is hard to feel dull when surrounded by such beauty.

Upon returning home I am concentrated with the American Beech experience. As I sit on my back porch removing my muddy boots, I am flashed with a clinical memory that I cannot shake. I hustle indoors to my bookshelf (The caveat here is this: I have often included the almost-homeopathic energetics of flower essences into herbal supplement mixtures for added emotional support for clients who have an affinity for such substances. I understand that many of you dear readers might roll your eyes at such ‘woo’). I open my book of Bach Flower Remedies, remembering the Beech within its pages. This is what I found for the Beech Flower Essence:

“For those who feel the need to see more good and beauty in all that surrounds them. And, although much appears to be wrong, to have the ability to see the good growing within. So as to be able to be more tolerant, lenient and understanding of the different way each individual and all things are working to their own final perfection.” – Dr. Edward Bach, The Twelve Healers and Other Remedies, 1936.

“My sentiments exactly,” I thought.

Acknowledgements

And so ends my journey into the rediscovery of American Beech, the chronicle of which I am grateful to have shared with you all. I would like to extend specific gratitude to Steven Foster for his support of my writing and photography as well as exposing me to the all-consuming world of historical literature online. I would also like to thank Andrew Lane Gibson for responding to my inquiry regarding the varietal classification of American Beech (and for his continued botanical inspiration). Both of these gentlemen have exceptional blogs that you should check out by clicking on their highlighted names. Thank you, dear reader, for paying attention to this post until the very end. This article has been republished from its original version with updated photos and edits.

Footnotes

1. Kirkbride, Elizabeth H. 1907. ‘A Winter’s Walk’ in The Friend: A religious and literary journal, printed by W.M.H. Pile’s sons, Philadelphia, Vol. 80, 1907, Fourth Month 20, 1907. Pg.322

2. Marcescent or marcescence, the term used to describe leave retention, is common with many oak species, and of course our beloved American Beech. Marcescent leaves are often more common with smaller trees or more apparent on lower branches of larger trees. Prolonged abscission period could indeed be an adaptive trait of the species better suited to more infertile soils. Escudero, A. and J.M. del Arco. 1987. Ecological significance of the phenology of leaf abscission. Oikos 49:11-14

3. The mixed mesophitic forest is defined as a climax community in which the dominant trees of the arboreal layer are Beech, Tuliptree, Basswood, Sugar Maple, Chestnut, Sweet Buckeye, Red Oak, White Oak, and Hemlock. Braun, L. 1950. The Deciduous Forests of Eastern North America. The Blackburn Press, Caldwell, NJ.

4. USDA Plant Profile database: Fagus grandifolia Ehrh. Accessed online [12/10/14]: http://plants.usda.gov/core/profile?symbol=FAGR

Also: Tubbs, C.H. and D. R. Houston. 1990. Fagus grandifolia Ehrh. Silvics of North America vol. 2: Hardwoods. Agriculture Handbook 654. U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Washington, DC. Accessed online [12/10/14]: http://www.na.fs.fed.us/pubs/silvics_manual/volume_2/fagus/grandifolia.htm

5. This is especially the case when scouring historical medical texts, as American physicians of old seemed to deem it so. Please see Henriette Kress online (Henriette’s Herbal Homepage) for various historical texts using the name Fagus ferruginea. Accessed [12/9/14]: http://www.henriettes-herb.com/

6. Camp, W.H. 1950. A biogeographic and paragenetic analysis of the American Beech(Fagus). Yearbook. The American Philosophical Society. Philadelphia. pp. 166-9. One could liken this differentiation to that of three different clans of Ent (J.R. Tolkien reference here folks), all looking like Ents and acting like Ents, but distinguished by their homelands and the pattern of tartans they wore (yes, I realize that Tolkein’s Ents did not wear tartans).

7. Kitamura, K and Shoichi Kawano. 2001. Regional Differentiation in Genetic Components for the American Beech, Fagus grandifolia Ehrh., in Relation to Geological History and Mode of Reproduction . Journal of Plant Research. Volume 114, Issue 3, pp 353-368.

8. Elias, Thomas S. 1971. The genera of Fagaceae in the southeastern United States. Journal of the Arnold Arboretum 52:159-195.

9. Although beech is now confined to the eastern United States (except for the Mexican population) it once extended as far west as California and probably flourished over most of North America before the glacial period (U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service. 1965. Silvics of forest trees of the United States. H. A. Fowells, comp. U.S. Department of Agriculture, Agriculture Handbook 271. Washington, DC.)

Also, Beech is prevalent in all nine of Lucy Braun’s forest regions of eastern North America, It is a characteristic species of four of those regions, and is dominant in two northerly regions including the namesake beech-maple and beech-birch-maple regions. It is prominent in most exemplary stands in the Northeast, as well as in many old-growth forests of the region (Braun, L. 1950. The Deciduous Forests of Eastern North America. The Blackburn Press, Caldwell, NJ.).

10. Henry Ward Beecher. Summer in the Soul. 1858

11. U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service. 1965. Silvics of forest trees of the United States. H. A. Fowells, comp. U.S. Department of Agriculture, Agriculture Handbook 271. Washington, DC.

12. American Beech is often found in the company of sugar maples (Acer saccharum), red maples (A. rubrum), yellow birch (Betula alleghaniensis), American basswood (Tilia americana), black cherry (Prunus serotina), southern magnolia (Magnolia grandiflora), eastern white pine (Pinus strobus), red spruce (Picea rubens), hickories (Carya spp.), and oaks (Quercus spp.), to name a few. Tubbs, C.H. and D. R. Houston. 1990. Fagus grandifolia Ehrh. Silvics of North America vol. 2: Hardwoods. Agriculture Handbook 654. U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Washington, DC. Accessed online [12/10/14]: http://www.na.fs.fed.us/pubs/silvics_manual/volume_2/fagus/grandifolia.htm

13. Michael Wojtech, M. 2001. Bark: A Field Guide to trees of the Northeast. University Press of New England, Lebanon, NH.

14. R.W. Shufeldt, C.M.Z.S. 1918. Studies of Leaf and Tree (Part II). American Forestry Vol. 24, No 289. American Forestry Association, Washington D C. Pg 100. Accessed online [12/12/14]: http://biodiversityheritagelibrary.org/page/20781520#page/111/mode/1up

15. U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service. 1974. Seeds of woody plants in the United States. C. S. Schopmeyer, tech. coord. U.S. Department of Agriculture, Agriculture Handbook 450. Washington, DC.

16. Thomas, M.C. & Schumann, D.R. 1992. Seeing the forest instead of the trees - Income opportunities in special forest products. Kansas City, Missouri, Midwest Research Institute.

17. Fernald, M.L., A.C Kinsey, and R.C. Rollins. 1958. Edible wild plants of eastern North America. Harper & Row.

18. Duke, J.A. 2000. Handbook of Nuts: Herbal Reference Library. CRC Press.

19. Turner, N.J. and P. von Aderkas. 2009. The North American Guide to Common Poisonous Plants and Mushrooms. Timber Press.

20. Allen, T.F and R. Hughes. 1874. The encyclopedia of pure materia medica: a record of the positive effects of drugs upon the healthy human organism. Vol 10. National Center for Homoeopathy (U.S.), donor. ; American Foundation for Homoeopathy, former owner. Boericke & Tafel, New York. Accessed online [12/17/14]: http://collections.nlm.nih.gov/bookviewer?PID=nlm:nlmuid-64240040RX10-mvpart. Allen and Huges recount the story of a 13 year old boy who had eaten a large quantity of beechnuts (what I believe to be of the European variety): “…Soon after eating the nuts he had been seized with torpor, gloominess, and dread of liquids. He had not been bitten by a rabid animal. Next (fifth day), seemed to talk more in his wildness and perturbation of mind, and his mouth flowed with foam more abundantly. Red and fiery urine with copious turbid white sediment, resembling and emulsion of beechnuts. ‘A few hours before he dies he vomited a poraceous bile, after which he died quietly.” Pg. 521.

21. Hamel, P. B., and M. U. Chiltoskey. 1975. Cherokee Plants and Their Uses – A 400 Year History. Sylva, North Carolina: Herald Publishing.

22. Pengelly, A. 2004. The Constituents of Medicinal Plants 2nd edition. CABI Publishing. United Kingdom.

23. Waugh, F.W. 1916. Iroquois Foods and Food Preparation. Ottawa: Canada Department of Mines.

24. Parker, A. C. 1910. Iroquois Uses of Maize and Other Food Plants. Albany, New York: University of the State of New York.

25. Moerman, D. E. 1998. Native American Ethnobotany. Timber Press, Portland, OR.

26. Herrick, J. W. 1977. Iroquois Medical Botany. Ph.D. Thesis, State University of New York, Albany.

27. Burlingame, J. 1826. The poor man's physician, the sick man's friend, or, Nature's botanic garden exhibited to view: its medical qualities unfolded, symptoms of diseases described, and cures made easy ; designed wholly for the use and benefit of families. Norwich, N.Y. Printed by Wm. G. Hyer for the author. Accessed online [12/20/14]: http://collections.nlm.nih.gov/catalog/nlm:nlmuid-2544072R-bk. In this text we find verbatim the musings of the above mentioned Nicholas Culpeper when Burlingame writes: “ The water found in decayed beeches, in hollows, will cure both man and beast, of any scurf, scab, or running sore. The leaves in poultice or ointment are very good to apply to hot swellings.” pg.113

28. Tobyn, Graeme. 1997. Culpeper’s Medicine: A Practice of Western Holistic Medicine. Element, United Kingdom. Nicholas Culpeper (1616 – 1654), a physician from London, England who practiced medial astrology and is remembered for his desire to deliver medicine to the common people from the confines of the wealthy and educated elite. During his time, all medical texts were written in Latin so that only those who could read Latin could use the information within the text. Nicholas Culpeper was ostracized by the Royal College of Physicians for translating medical texts from Latin to English and was eventually expelled from the College.

29. Culpeper, Nicholas. 1652. The English Physician. Also, 1653. The Complete Herbal. Now found at the following references: Culpeper, Nicholas. 1800. The English Physician Enlarged : With Three Hundred and Sixty-Nine Medicines, made of English Herbs, that were not in any impression until this. Being an astrologo-physical discourse of the vulgar herbs of this nation ... . Barker, London. Digital edition by the University and State Library Düsseldorf and Culpeper, Nicholas (1995). Culpeper's Complete Herbal: A Book of Natural Remedies of Ancient Ills (The Wordsworth Collection Reference Library) (The Wordsworth Collection Reference Library). NTC/Contemporary Publishing Company.

30. According to The American Heritage Dictionary (https://ahdictionary.com/), tetter is a term for “any of various skin diseases, such as eczema, psoriasis, or herpes, characterized by eruptions and itching.” Apparently, there are many kinds of tetter, including moist, branny, scally, scald-head, salt-rheum, and running tetter.

31. Weiss, MD, R.F. and V. Fintelmann, MD. 2000. Herbal Medicine. 2nd ed. Thieme, Stuttgart, Germany.

32. Grieve. M. 1931. A modern herbal. Vol. 1. Harcourt, Brace & Company, New York

33. For a thorough overview of the traditions of American medicine: Traditions in Western Herbal Medicine by Peter Mackenzie-Cook, DBTh, FETC. In The Herbalist, newsletter of the Canadian Herbal Research Society. Copyright June 1989. Available online: http://www.henriettes-herb.com/faqs/medi-5-3-1-western.html For more information about Physiomedicalism: http://www.physiomedicalism.com/

34. Hollembaek, H. and Foorte, A.E. 1865. The American Eclectic Materia Medica: containing on hundred and twenty-five illustrations of trees and plants of the American Continent. H Hollembaek , Philadelphia.

35. Cook, MD, W.H. 1869. The physio-medical dispensatory: a treatise on therapeutics, materia medica, and pharmacy, in accordance with the principles of physiological medication. by Wm. H. Cook, M.D., professor of botany, therapeutics, and materia medica in the Physio-Medical Institute; late professor of surgery in the Physio-Medical College of Ohio. Cincinnati: published by Wm. H. Cook, no. 101 West Sixth-Street 1869. The Physiomedical Dispensatory, 1869, was written by William Cook, M.D. Available online at: http://medherb.com

36. King, J. 1854. The American Eclectic Dispensatory. Cincinnati : Moore, Wilstach, & Keys. Accessed [12/15/17]: http://collections.nlm.nih.gov/catalog/nlm:nlmuid-61660590R-bk

37. Moriguchi N1, Sato A, Shibata T, Yoneda Y. 2011. [A historical review of the therapeutic use of wood creosote. Part II: Original plant source of crude drug wood creosote]. Yakushigaku Zasshi. 2011;46(1):13-20. Accessed online [12/17/14]: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22164686

38. Wood tar creosote was discovered as the principle of meat smoking and became used as a replacement for the smoking process, Ambrose, A. and E.G. Smith. 1857. The preservation of food: From the "Aus der natur" of Abel. Press of Case, Lockwood and company.

39. Carpenter, R.D. 1974. American Beech. American Woods, FS-220. US. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service July 1974. Accessed online [12/15/14]: http://biodiversityheritagelibrary.org/item/160811#page/1/mode/1up

40. Allen, Alfred Henry (1910). "Creosote and Creosote oils". Allen's commercial organic analysis (P. Blakiston's Son & Co) 3: 346–391.

41. ATSDR (Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry, Division of Toxicology, Public Health Statement, Creosote, Cas # Wood Creostoe 8021-39-4, September 2002) Accessed online [12/17/15]: http://www.atsdr.cdc.gov/phs/phs.asp?id=64&tid=18

42. Connell, W. F., Grant M. Johnston, and Eldon M. Boyd. 1940. On The Expectorant Action Of Resyl And Other Guaiacols. Can Med Assoc J. Mar 1940; 42(3): 220–223. Accessed online [12/17/15]: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC537807/

43. Powers, S.K and H.T. Howley. Exercise Physiology: Theory and Application to Fitness and Performance. 7th Edition. Available online: http://www.ipmr.kmu.edu.pk/sites/ipmr.kmu.edu.pk/files/Lectures/Endo-1.pdf

![A dancer of an Iroquois False Face Society. Image compliments of Popular Science Monthly (1892), Vol. 41., New York, Popular Science Pub. Co., etc. Pg. 740. Accessed online [1/1/15]. Click image to for source url.](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/58a38323bf629a3dbe8ce7e2/1610215840454-W6J6AGUALEVP49W9Q4RY/iriquois+false+face+society.jpeg)